F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, 168" x 204"

(Photo by John Reddy)

This prominently placed, apocryphal mural honors the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, which made American settlement of the West possible. Depicted are the two heads of state, French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and U.S. President Thomas Jefferson (who never actually met), the Marquis de Barbé-Marbois (lead negotiator for the French), Robert Livingston (lead delegate for the United States), and future president James Monroe, who conducted the negotiations. Behind the men is an image of the Sphinx and Egyptian pyramids—possibly an allusion to Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign, but more likely a reference to Masonic imagery.

F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, 168" x 204"

(Photo by John Reddy)

Strategically placed opposite The Louisiana Purchase hangs Custer’s Last Battle, which commemorates the death of George Armstrong Custer and the other army casualties at the Battle of Little Bighorn (Battle of the Greasy Grass) in eastern Montana on June 25, 1876. In order to better fit the setting, Pedretti artists reduced the battle scene to a stark confrontation between Custer and an unidentified Lakota warrior.

F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, 168" x 102"

(Photo by John Reddy)

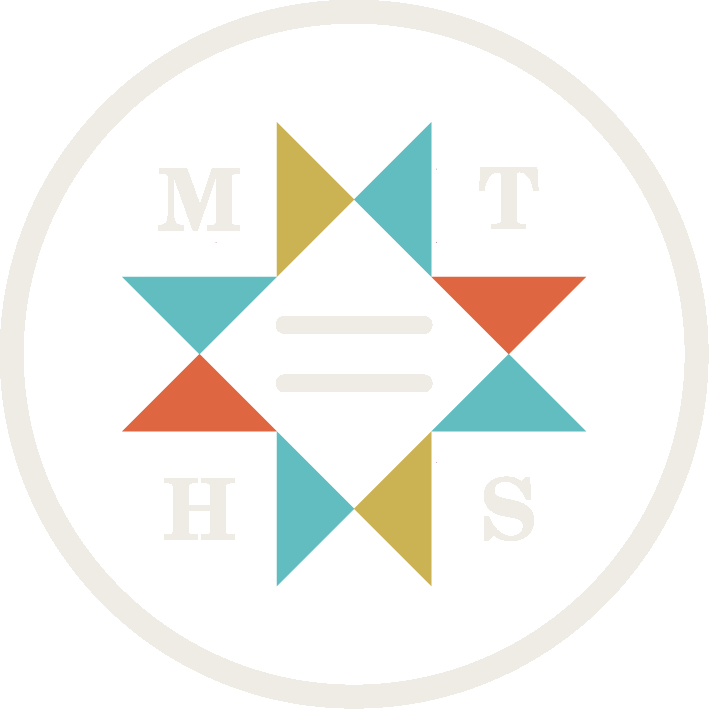

Old Fort Benton extends the theme of the fur trade beyond the romantic individual trapper celebrated in the Rotunda to recognize it as a complex, international business.. Pictured are two well-known associates of the American Fur Company, which founded Fort Benton. Seated is Pierre Chouteau, Jr. (1789–1865), grandson of the founder of the city of St. Louis and inheritor of his family’s fur business. Scottish-born Andrew Dawson (1817–1871), standing, ran Fort Benton between 1854 and 1865. Fort Benton—shown as a sprawling group of adobe brick buildings in the upper right—was one of Montana’s principal trading centers until the construction of the railroads. Tepees brushed in light reference the fort’s original purpose: to expand market possibilities among the Blackfeet Indians.

F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, 168" x 102"

(Photo by John Reddy)

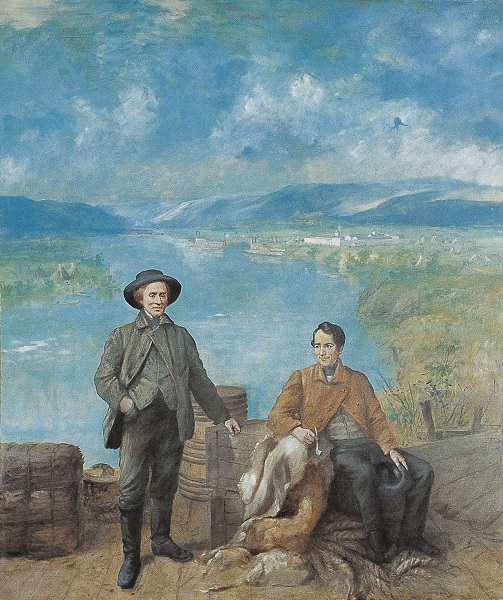

Old Fort Owen, the titular subject, is relegated to the distant background; instead, two Jesuit priests, Anthony Ravalli, S.J. (1812–1884) and Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J. (1801–1873), dominate the image. (The Salish child tucked under Ravalli’s arm is a touch borrowed from depictions of the infant Christ in Italian Renaissance painting.) A legendary figure in Montana history, Belgian-born De Smet established St. Mary’s Mission in the Bitterroot Valley in 1841 in response to requests from several Indian delegations; Italian-born Ravalli followed five years later. When the mission closed in 1850, Major John Owen (1818–1889) purchased the building and developed the popular trading post that bore his name.

F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, 168" x 102"

(Photo by John Reddy)

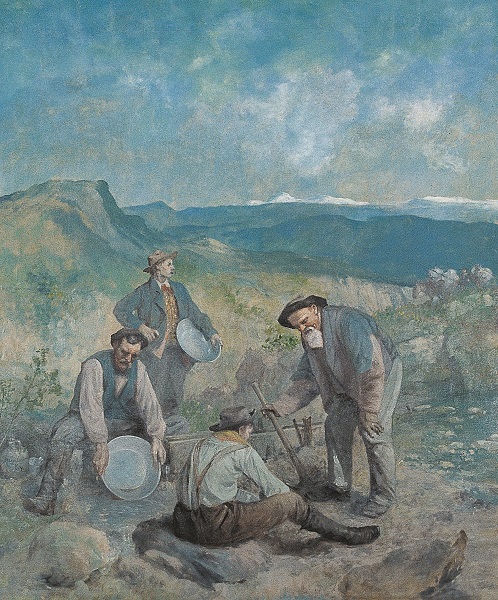

Prospectors at Nelson Gulch depicts four men performing various tasks connected with placer mining, the original and most primitive phase of mining in Montana. The figure at the right leaning over the pan is Jerry Robinson, while the man seated on the sluice is Isaac “Ike” Newcomer, two well-known old-timers who came to Montana in the 1860s. Although not one of the most famous mining sites, Nelson Gulch, located outside of Helena, enjoyed a high degree of productivity. The scene is romantic and nostalgic, depicting a scene far different from the heavily industrialized mining that had evolved by 1902.

F. Pedretti’s Sons, oil on canvas, 1902, 168" x 102"

(Photo by John Reddy)

In July 1805, Meriwether Lewis (1774–1809) and William Clark (1770–1838) reached a juncture critical to their journey: the Three Forks of the Missouri, where the Madison, Gallatin, and Jefferson Rivers flow together. Pictured are Lewis (standing) and Clark (seated), Clark’s slave York, and Indian interpreter Sacagawea. Although the painting details a historic event, it is important to note that many aspects of the painting—particularly the way York and Sacagawea are depicted—are not accurate. This painting reminds viewers that the Pedrettis were paid as decorators, not historians.

Eugene Daub, bronze bas relief, 2006, 96" x 204"

(Photo courtesy Tom Ferris for MHS)

The Montana Historical Society cooperated with the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Commission to bring this piece to the Capitol’s halls. Artist Eugene Daub (born 1942), of San Pedro, California, was selected through a nationwide competition. Installed in the Capitol’s Senate chamber in 2006, We Proceeded On shows the Corps of Discovery at the High Cliffs area, east of Great Falls. The oarsmen’s straining muscles emphasize the demanding physical labor that Corps members endured. Sacagawea’s presence at the center of the bronze pays homage to the state’s Native American tribes, who called this place home long before Euro-Americans began to venture west.